Research Paper on Restaurant Culture in the United States

1. Introduction

Restaurants, large and small, play a significant role in the lives of all Americans in today’s society. Many people start their morning with a hot and steamy cup of coffee from their local diner or end their day with dinner at a trendy restaurant to celebrate their long work day. This paper will touch on the function of restaurants in discovering a place of comfort, leisure, and social interactions outside of the everyday obligations. It will connect these ideas to our historical practice of nomadism within a hunting and gathering lifestyle. There are so many details that go into creating a restaurant’s atmosphere whether that be the physical design and ambiance, the intricacies of a menu, or the sourcing of the ingredients. It is important to identify the presence of these miniscule details to understand why restaurants have obtained such a significant presence in U.S. cuisine culture.

2. The Third Place

2.1 Contemporary Third Place

The sun rises, we wake up, go to work, go back home, the sun sets, and repeat. This cycle can make us feel stagnant in a world that is constantly and quickly evolving and changing. There are these rare moments, where people can gather without the desire to constantly check the clock. Friends can congregate in places at a leisurely pace. Urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg referred to these locations as the “third place,” with home being the first and work being the second (Livini 2025). Oldenburg defined a third place as “a generic designation for a great variety of public places that host the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work” (Christensen 2008).

These third places often take the form of a restaurant. Friends, family, and strangers can gather around a table, booth, or bar and share meals and stories to forget about the business meeting they have the next day or the electric bill that has sat in their apartment untouched. For years, restaurants have become spaces to find love, laughter, and good food. This “third place” as a restaurant reinforces the idea of food as a symbol. Food can stand as a function of a relationship, and in this instance food symbolizes a moment of gathering and leisure (Ulibarri 2025).

2.2 Hunting for your Third Place

Up until about 10-15 thousand years ago, our lives practically revolved around finding food within a hunting and gathering system (Ulibarri 2025). This mode of obtaining food led to a nomadic lifestyle. In order to find substantial resources, hunting and gathering tribes had to constantly be gravitating towards new land. While these communities may not have been able to make reservations for the newest restaurant as a means of relaxation outside of work, they had the ability to discover idleness from their workload within their society. In a study on work-life balance, James Gangwisch pointed out that it only required about 20 hours of work a week to collect and prepare food, while in contemporary U.S. society, a work week consists of around 40 hours (Gangwisch 2014). Deliberate effort must be put in to find downtime from the hustle and bustle of work and home life.

This is a relatively new notion in reference to the hunting and gathering work life balance. Richard B. Lee breaks down the “traditional view that hunting and gathering people live on the edge of survival” (Lee 1968). Lee studied the !Kung Bushmen of Botswana who inhabit the northwest region of the Kalahari Desert. Lee says, “it is certainly true that getting food is the most important single activity in Bushman life,” but his research reinforces Gangwisch’s ideas that “despite their harsh environment, [the adults of the Dobe camp] devote from twelve to nineteen hours a week to getting food” (Lee 1968). Lee details the leisurely activities of women in the camp. When a woman is done gathering a sufficient amount of food for her family, she “spends the rest of her time resting in camp, doing embroidery, visiting other camps, or entertaining visitors from other camps” (Lee 1968). The men have similar activities of visiting, entertaining, and dancing as a break from their strenuous hunting practices.

A “third place” has always been a component in the lives of humans. As work weeks become more intense, we as a society have to exercise a more dedicated effort to set aside time to connect with other people and connect with new environments. Gwendolyn Purifoye, an assistant professor at the University of Notre Dame, commented on the significance of a “third place,” saying that,“Public leisure space is critical for society. If you don’t build places to gather, it makes us more strange, and strangeness creates anxiety” (Livini 2025). We have a long history of gathering, now we need to devote time to gathering ourselves. A consistent and popular destination for this meeting place will always be a restaurant.

3. The Physical Space of the Third Place

The Project for Public Spaces is a nonprofit in New York that plays a role in helping to create community-powered public spaces. The organization touched on Oldenburg’s perspectives of community oriented public spaces by saying, “[A] third place allows an individual to put aside their worries and concerns and simply enjoy the company and conversation around them” (Christensen 2008). As streets are now lined with a plethora of restaurant options, these businesses are finding new ways to stand out. In hunting and gathering civilizations, people were not concerned about the ambiance or “vibe” of the land. They focused on whether or not it could provide them with a sufficient means of energy. Now where people go to gather with friends or family and “gather” their food, there is a heightened emphasis on physical space and branding.

3.1 Appreciation of Ambiance

Anna Polonsky, the founder of a Brooklyn design studio, says that restaurants need to be “Fun, stylish, and full of energy, with great drinks, good enough food and an atmosphere they can’t replicate at home” (Krishna 2025). This is similar to the idea of a restaurant as a “third place,” people are searching for an ambiance that differentiates from their “first place,” also known as “home.” This emphasis on design adds a new level of authenticity for the people behind the restaurant. In a New York Times article titled, “Is the Restaurant Good? Or Does It Just Look Good?,” Priya Krishna, an interim restaurant critic, says, “Restaurateurs don’t just want a dining room that looks nice — it has to be personal” (Krishna 2025). The creativity aspect allows restaurateurs to express themselves through their business, and create genuine locations for Americans to find their “third place.” Polonsky adds, “Now, in both branding and interiors, there is more and more a desire to create your own story” (Krishna 2025).

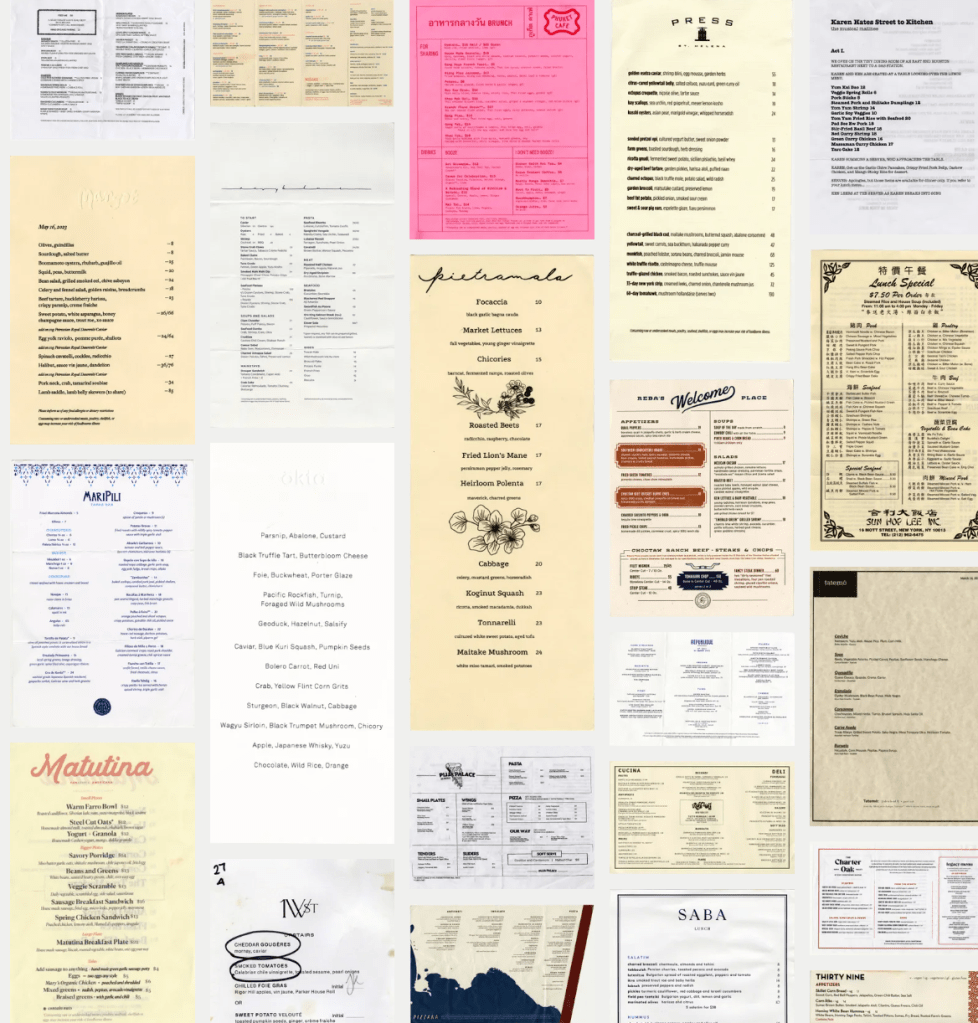

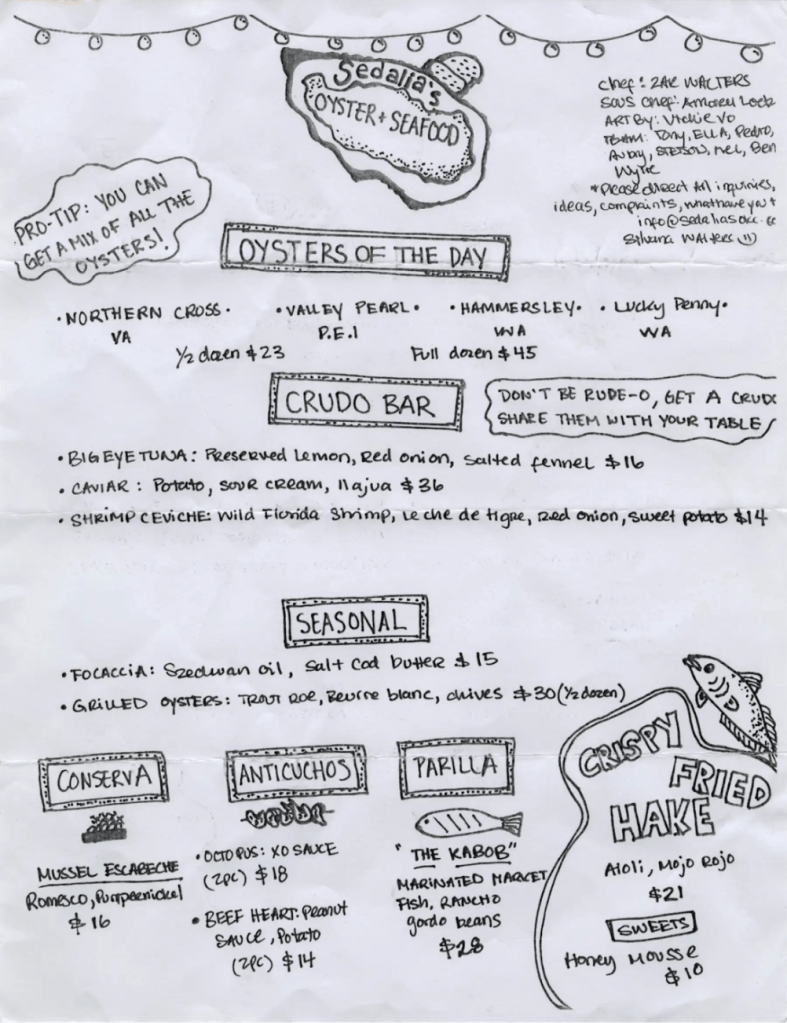

3.2 Menu Intricacies

Another component of storytelling within US dining is creation of the menu, a concept that heavily contrasts the ancestral method of discovering food. We have this opportunity because of a surplus of food, an easy access to food, and continual increase of variety of food (Ulibarri 2025). The New York Times recently conducted a study on “The Menu Trends That Define Dining Right Now.” Through the observation of 121 menus, they categorized the trends into three different sections: food, aesthetic, and anatomy (Krishna, et al 2024). They determined that the menu landscape is filled with Caesar salads, caviar, yuzu, fried chicken, nostalgic desserts, and panna cotta. Menus are leaning into bolder and brighter colors, smaller fonts, and the inclusion of illustrations. Within the anatomy category, their study revealed that “restaurateurs are using limited menu real estate to signal their commitment to staff,” like added service charges to benefit staff wages. They are also setting aside sections for non-alcoholic drink options or relying on one menu that is plastered on the wall of the restaurant with minimal text (Krishna, et al 2024). The enhanced focus on the miniscule details of a dining establishment is transforming eating to an orchestrated event that provides a planned time for leisure and entertainment opposed to a necessary act for nourishment. It could be argued that meals now play a role in nourishing our desire for social interactions, downtime, and ease.

Menu from Sedalia’s Oyster and Seafood, Oklahoma City

4. Farm-to-Table

The New York Times menu study also pointed out that the farm-to-table movement inspired menus to list all the local suppliers they utilize to highlight the establishment’s role in the transparency of local and organic ingredients (Krishna, et al 2024). The farm-to-table movement emphasizes the importance of restaurants relying on local agriculture to supply their menu. The term “farm-to-table” is trending today but became prevalent as early as 1914. The movement began as an initiative created by post offices with a goal to transport farm-fresh produce from rural to urban cities as directly and quickly as possible (National Agriculture Library). The postal program started to gain traction with journalists. An excerpt from a newspaper called, “Charlevoix County Herald” out of Michigan says the “program was a way for producers to make money by selling those farm goods that would otherwise go to waste” (National Agriculture Library).

Newsclipping from “The Washington Times” July 20, 1916

Globally, there is about one billion tons of food wasted each year. (Ulibarri 2025). Just in an average household in the U.S. and Canada, 15-25 percent of groceries are wasted. (Baldwin 2014). This is not only a waste of the produced food, it is a waste of the resources used for the production of that particular food. To be specific, 4% of all energy we are utilizing in the creation of food, we ultimately throw away (Baldwin 2014). This food waste decomposes and creates gasses that lead to climate change (Ulibarri 2025).

In 1971, in Berkley, California, the restaurant “Chez Panisse” was founded by chef Alice Waters. Now over 50 years later, we have Waters to thank for helping pioneer the farm-to-table restaurant model (Brinkley, et al. 2022). Waters was inspired by the dining and cuisine culture of the French. In France, there is less stress and more pleasure in relation to eating. They tend to celebrate their meals, rather than highlight the consequences (Ulibarri 2025). Waters really embraced the French practice of focusing on quality of ingredients rather than the quantity. By establishing an emphasis on locally grown and seasonal produce to create dishes, the farm-to-table movement began to flourish. With this, “Chefs and restaurants are uniquely positioned in the food system to both generate consumer interest in certain food quality attributes and motivate farmers to grow such products” (Brinkley, et al. 2022).

Vern Grubinger, a professor and the vegetable and berry specialist at the University of Vermont, composed a list of “Ten Reasons to Buy Local Food” (Grubinger 2010). In this, he explains that local food tastes and looks better, is better for you, preserves genetic diversity, is safe, supports local families, builds community, preserves open space, keeps taxes down, benefits the environment and wildlife, and is an investment in the future (Grubinger 2010). By directly traveling from the farm to the restaurant table, it is less likely that the fresh foods will lose its natural nutrients. Grubinger points out that by cutting out the middleman and selling straight to the restaurants and consumers, farmers are able to acquire the “full retail price for their food – which helps farm families stay on the land” (Grubinger 2010). Not only are restaurants able to actively support local economies and families through this proactive, they can positively impact the environment by reducing carbon, conserving fertile soil, and protecting water sources. He finalizes his argument by saying, “By supporting local farmers today, you are helping to ensure that there will be farms in your community tomorrow” (Grubinger 2010).

By embracing a farm-to-table identity, restaurants are able to create a “third place” that benefits the partakers, the local producers, and protects the land that has provided our cuisine for millions of years.

5. Nomadic Restaurants

Due to the distribution of food, hunting and gathering societies often had to embrace a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle to follow “the natural migration of animals and seasonal variation of foods” (Ulibarri 2025). Now we are at a place in society where a “hunt” for food can look like walking only a few minutes to get to your nearest restaurant, especially in urban cities. But, it appears that even 15 thousand years later, we are resorting back to old ways and finding trends in traveling food. These “pop-up” restaurants are temporary dining experiences that the New York Times describes as a place “where chefs temporarily set up shop in a dining room, a barn or even a dorm room, [where] dinner is an improvisation, more jazz than symphony. For a limited time and a limited audience, a cook can riff with premeditated spontaneity” (Nierenberg 2020). Ranging from a few hours to several weeks, pop-ups bring new opportunities to restaurant-goers who want to experience new cuisine and a new ambiance. It also provides chefs and restaurateurs the chance to explore new cuisine and design to tell their stories to a new crowd in a new location. Food can be used to reflect our individual identities and a way to present who we think we are (Ulibarri 2025). Pop-up restaurants allow chefs the ability to experiment with expressing themselves in unique ways and in original places through the kitchen. It is like offering themselves up on a silver platter.

“Nomadism is a way and a result of adapting to the natural and economic situations” (Otunchieva 2021). This constant adaptation and relocating made the idea of land ownership a very foreign concept for nomadic civilizations. Land was viewed as communal and “was associated with belonging to a tribe, group of people or a state” (Otunchieva 2021). If these ideas are applied to pop-up restaurants, it allows us to view the temporary culinary establishments as spaces driven by community and the sharing of meals and identity. The restaurateurs and consumers are adapting to the social and culinary trends to create these tastes and atmospheres that bring people together to have a shared moment and a shared cuisine. Food section editor at the New York Times, Nikita Richardson, describes these trendy ephemeral dining spaces by saying “They’re here today, gone tomorrow…With pop-ups, it’s all about the thrill of the hunt,” truly connecting us with our history (Richardson 2024).

6. Conclusion

Restaurants have become a special place for people to express themselves whether it be through consumers sharing stories with friends and families to decompress from everyday life or chefs creating meals and menus from local and organic ingredients. Utilizing these dining establishments as spaces for leisure allows us to connect with our historic practices of hunting and gathering through finding time for ourselves outside of work and home. Restaurateurs devote so much time and energy to meticulously selecting the physical aspects of the restaurant to enhance the ambiance and experience of partakers. When these restaurateurs also choose to incorporate local suppliers into their decision making, they are helping to benefit the consumers’ health, smaller farms, and the environment. Food has the ability to symbolize identities and restaurants are the perfect canvas for a chef or consumer to reflect on the story of our historical dining practices and grow the future of American dining.

Works Cited

Baldwin, Grant. “Just Eat It: A Food Waste Story.” YouTube, produced by Jenny Rustemeyer Apr. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=KUHdTDwdq8U. Accessed 7 Jul 2025.

Brinkley, Catherine, et al. “Can a Farm-to-Table Restaurant Bring about Change in the Food System?: A Case Study of Chez Panisse.” Food, Culture, & Society, vol. 25, no. 5, 2022, pp. 997–1018, doi: 10.1080/15528014.2021.1948754.

Christensen, Karen. “Ray Oldenburg.” Project for Public Spaces, 31 Dec. 2008, www.pps.org/article/roldenburg

Gangwisch, James E. “Work-Life Balance.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 7, Jul. 2014, pp. 1159–1160, National Library of Medicine, doi:10.5665/sleep.3826.

Grubinger, Vern. “Ten Reasons to Buy Local Food.” University of Vermont, Apr. 2010, www.uvm.edu/vtvegandberry/factsheets/buylocal.html.

Krishna, Priya. “Is the Restaurant Good? Or Is It Just the Ambience?.” The New York Times, 9 Apr. 2025 www.nytimes.com/2025/04/09/dining/restaurant-ambience-vibes.html.

Krishna, Priya, et al. “The Menu Trends That Define Dining Right Now.” The New York Times, 25 Jan. 2024, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/01/22/dining/restaurant-menu-trends.html.

Lee, Richard. “The Hunters: Scarce Resources in the Kalahari.” Man the Hunter, edited by Irven DeVore, Aldine Publishing, 1968.

Livni, Ephrat. “Where Have All the ‘Third Places’ Gone? .” The New York Times, 28 Feb. 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/02/28/business/third-place-meaning-starbucks.html.

National Agriculture Library, “Mailboxes, Mom and Pop Stands, and Markets: Local Foods Then and Now.” National Agriculture Library Digital Exhibit, www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/ipd/localfoods/exhibits/show/farm-to-table/background-and-origins. Accessed 13 July 2025.

Nierenberg, Amelia. “Pop-up Dinners That Share a Culture, Course by Course.” The New York Times, 28 Jan. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/01/28/dining/pop-up-dinners.html.

Otunchieva, Aiperi, et al. “The Transformation of Food Culture on the Case of Kyrgyz Nomads—A Historical Overview.” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 15, 2021, p. 8371, doi: 10.3390/su13158371

Richardson, Nikita. “Restaurant Pop-Ups Are about the Thrill of the Hunt.” The New York Times, 14 Mar. 2024, www.nytimes.com/2024/03/14/dining/restaurant-pop-ups-nyc.html.

Ulibarri, Lawrence. “8, Food Idology 220.” Anthropology 220: Nutritional Anthropology, 2025, University of Oregon. Online Lecture. YouTube ,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A0d-VoLmyNo. Accessed on 1 Jul. 2025.

Ulibarri, Lawrence. “12. Issues and Solutions.” Anthropology 220: Nutritional Anthropology, 2025, University of Oregon. Online Lecture. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I4nSc5ZlApg. Accessed on 6 Jul. 2025.

Ulibarri, Lawrence. “1, part 1, Basics.” Anthropology 220: Nutritional Anthropology, 2025, University of Oregon. Online Lecture. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8vITQ3jtGXY. Accessed on 23 Jun. 2025.